Since the establishment of the New York Stock Exchange in 1792, Manhattan’s Wall Street has been home to the nation’s largest commercial markets and is regarded today as the beating heart of American capitalism and global finance. Located thousands of miles west of those glimmering skyscrapers and neoclassical facades, Los Angeles’ Wall Street offers quite a different landscape: running between the Fashion district, Little Tokyo, and the sprawl of warehouses near the Los Angeles River, Wall Street is the heart of L.A.’s skid row, home to some 8,000-10,000 people experiencing homelessness, a symbol of the misery and gross inequities that capitalism hath wrought. And yet it was there, in a small restaurant amidst brick storefronts and residential hotels on Wall Street, that a group of 45 Sephardic Jewish immigrants gathered in February 1917 and established the Sosiedad Paz i Progreso (Peace and Progress Society), one of a handful of organizations that merged to form today’s Sephardic Temple Tifereth Israel. Most were young men born in Rhodes, an island off the coast of Turkey in the eastern Mediterranean, who had come to Los Angeles in the previous decade and lived in boarding houses and small cottages nearby. A few worked as clerks or salesmen, but the majority of those in attendance made their living as bootblacks shining shoes in stands and on street corners downtown. Rooted in a blend of kinship and commercial ties, immigrant landsmanshaft and entrepreneurial street hustle, the solidarity among these bootblacks of Wall Street served as the foundation of the Sociedad and in turn Sephardic Jewish life in Los Angeles as a whole.

A Brief History of Boot blacking in Los Angeles

Boot blacking has traditionally been associated with street children – runaways and orphans who used their cunning and moxie to eek out a living, an image popularized in dime novels like Horatio Alger’s Ragged Dick (1868). Boot blacking, after all, was a job one got “on the street,” requiring very little to no overhead investment nor a fixed location; for just the cost of a kit of brushes and polish, a bootblack could offer nickel shines on any street corner. Like newsies, messenger boys, and bet takers, bootblacks sometimes worked at the behest of older “artful dodgers” or other unsavory characters who forced them on to the street and claimed a portion of their profits. Such practices were a cause of great concern among social workers and progressive reformers, whose efforts to raise public awareness about the exploitation of street children further entrenched the association of boot blacking with kids. In other cases, groups of young, streetwise bootblacks self-organized, working together in well-trafficked areas to manipulate prices and scam their well-to-do customers, methods that frequently the drew attention of local police. In 1911, for example, the Los Angeles Times reported that the LAPD executed a round-up of “the largest and strangest gang of organized street bandits that ever infested Los Angeles”: a group of 50 bootblacks, all of whom were under the age of 11 and most of whom easily escaped arrest. While the Times reporter seemed to appreciate the humor of the scene that unfolded, he also sympathized with the LAPD’s concern, describing that while the gang’s weapon of choice – their twelve-pound boot blacking kits – might not seem as dangerous, “when swung at arms length by the sinewy arm of the children of the street, they are formidable weapons.”1

This informal, underground economy also had a formal sector comprised of shoeshine stands in barbershops, fine men’s clothiers, and the lobbies of banks, department stores, and office buildings downtown. Those working at the stands were mostly older, more experienced bootblacks, many of who were African American men, and who, after years of shining on the streets, forged symbiotic relationships with building and business owners. The stands offered bootblacks both safe and secure spaces to work as well as built-in customer bases, so long as freelancing competitors did not set up shop outside. Accordingly, these bootblacks also self-organized as a means of protecting their “turf”: in 1901, they launched an effort to establish a Bootblacks’ Union, following on the model set by the city’s barbers who had successfully raised the price of a shave from five cents to ten.2 Although the campaign failed to affect a uniform price scale, it reflected the bootblacks’ desire to challenge their reputation as wily street hustlers and assert themselves as skilled craftsmen, deserving of higher compensation for their labor. When the Bootblacks’ Union moved again to increase the rates for shines in the city in 1907, its representatives insisted to the Times that “practically every member of the bootblacks’ ‘profession’ in Los Angeles is a member of the union,” a sign that union organizing had effectively convinced the city’s bootblacks to embrace a collective identity as professionals. Unfortunately, that the Times reporter inserted quotation marks around the word “profession” suggests the wider public had not yet been persuaded of the same.3

Unionization had its consequences, however, as the demographics of Los Angeles’s shoe-shine industry shifted in its wake. As ever more bootblacks began charging the union rate for their shines, a new group of workers began undercutting their prices, a group that both contemporary observers referred to as “the Greeks.”4 While there is no extant data to confirm this demographic shift beyond anecdotal references to “Greek immigrants invading” the local shoe-shining industry, it is likely that many, if not most, of these new bootblacks were not, in fact, Greek immigrants but rather Sephardic Jews from the island of Rhodes.

A Brief History of Jewish Life in Rhodes

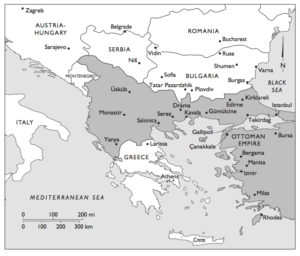

Located in the southeastern Aegean Sea, just over ten miles from the Anatolian coast of southwest Turkey, Rhodes had been an important outpost of maritime trade between East and West since the days of Greek antiquity and served as a regional administrative center of the Byzantine Empire. In the fourteenth century, the island was occupied by Christian crusaders, who erected a large gothic-style castle and fortress (known as the Palace of the Grand Master) on a hill overlooking the main harbor connected to thick stone walls encircling the capital and central market to defend the island from repeated attacks by the Ottoman Empire. But in 1522, Ottoman Sultan Suleiman “the Magnificent,” with an army of tens of thousands of troops, finally captured the island, the empire retaining their control for nearly 400 years.

Suleiman instituted the Ottoman millet system on the island, granting non-Muslim ethno-religious communities the freedom to worship and the right to autonomous self-governance over religious matters, education, and civic regulations in exchange for communal taxes. While the application of the system restricted Jewish residence on the island to a segregated neighborhood inside the city walls known as the judería (Jewish quarter), it also afforded Jews a degree of social and economic mobility unavailable in Christian Europe at the time, drawing hundreds of new Jewish settlers, including those expelled from Spain in 1492, to the island. Although smaller in population size, like Smyrna, Salonika, and Istanbul, Rhodes became an important center of Sephardi Jewish life.

In the nineteenth century, L’Alliance Israélite Universelle, a French-Jewish philanthropy, opened a school in Rhodes near the Kahal Grande (“Great Synagogue”), offering classes in math, the sciences, literature, and world history in French for local children. Guided by assimilationist ideals consistent with the French colonial mission civilisatrice, the Alliance viewed the traditional communal structure, folkways and social customs that predominated in the judería as backwards and hoped that by providing a “western” alternative to religious education they could transform the “Oriental” Jews of Rhodes into modern subjects. These ambitions coincided with the westernizing impulse of the Tanzimât (1839–1876), when the Ottoman government reorganized the empire by centralizing banking and civil administration, modernizing infrastructure, and implementing new legal and constitutional reforms that extended equality with regard to property rights, education, and civil service to all Ottoman subjects regardless of religion. Some Jewish families in Rhodes became model Ottoman “imperial citizens,” using their multilingualism–fluency in French and Ladino, and sometimes Greek and Turkish as well–to build transnational commercial networks and lucrative import-export businesses. Salomon Alhadeff, for example, grew the small store his father founded in 1819 into a global tobacco enterprise with branches in Smyrna, Mersina, Athens, and Milan. Traders and wholesale merchants like Alhadeff were also among the first Rhodeslis to immigrate to Europe and the United States.

But by 1900, most of the 4,000 Rhodeslis who lived in the judería maintained more traditional patterns of living despite these developments. Indeed, very few of the modernization projects initiated during the Tanzimât had reached Rhodes: most of the island had no plumbing or access to clean water, no electricity or paved roads, and no banking or monetary system. Most Jewish men made their livings as craftsmen–tanners, cobblers, carpenters, tailors, and coppersmiths–or as petty merchants, rag dealers, and junk peddlers. And while some Jewish women supplemented their family income by spinning silk or sewing, they worked almost exclusively in the home and were expected to perform to all domestic and child-rearing tasks. As industrialization and mass production in Europe drove down the cost of consumer products, young Rhodeslis–whose expectations for their futures had been shaped by their “western” education–confronted dwindling career prospects and chose to seek out new opportunities in Brazil, Argentina, the Belgian Congo, South Africa, and the United States.

Rhodesli emigration accelerated following a series of geopolitical developments–beginning with the Young Turk Revolution in 1908–that destabilized the Ottoman Empire and Jewish life throughout the Ottoman world. Sensing the weakness of the Ottomans’ hold on the island, an increasingly expansionist and stridently nationalist Italy invaded Rhodes in 1911, hoping that they might use the island as leverage to negotiate an Ottoman withdrawal from Libya. Distracted by a more urgent conflagration in the Balkans–where Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia, and Montenegro had all declared was against the empire in 1912–the Ottomans agreed to surrender Libya with the promise that Rhodes would be returned. But the Italians did not leave: the conflict in the Balkans could not be contained, the Ottomans lost most of their European holdings, and before they could reclaim the island, the Great War had spread across Europe and the Middle East. Confronted with an Ottoman Empire that was rapidly being dismembered and an uncertain future under Italian rule, more Rhodeslis left the island to join friends and family living elsewhere.

By 1924, when the United States implemented new, restrictive quotas that effectively cut off immigration from southern Europe and the Mediterranean, about half of the Jewish population of Rhodes had left the island. Young men typically emigrated first, some with the intention of returning after the situation on the island improved, only to later send for their wives, children and family members. Small, but vibrant Rhodesli communities emerged across the globe–from Cairo and Buenos Aries to Katanga and Jerusalem, as well as in New York, Seattle, Atlanta, and Portland. One of the largest of these was in Los Angeles, where an estimated 400 Rhodesli immigrants settled by the 1930s.5

Rhodesli Bootblacks Take Los Angeles

When Louis Israel arrived in Los Angeles in the fall of 1916, the city’s main passenger terminal was La Grande Station, an ornately decorated brick building with a large, Moorish dome located at the end of 2nd Street near the banks of the L.A. River. Louis was a graduate of the Alliance school and had left Rhodes at the age of fifteen to earn money to support his widowed mother and sister, staying in New York for a time before setting out to make a new life in the west. From the station, he walked ten blocks north to the Bixby Hotel at the corner of 4th and Wall Streets, where he could rent a small furnished room with a shared bathroom for $2 a week. The Bixby may very well have been his intended destination, as it was home to three other Rhodeslis who shared his surname: Bohor, Mike, and Sam Israel, all born in Rhodes a few years before Louis, lived just a few doors down the hall. So too did Yehuda, Morris, Louis and Abraham Cohen, Isaac and Victor Alhadeff, Louis and Jake Menashe, Morris Hassan, and Albert Aruzadel. Because Rhodes was home to many large and interconnected Jewish families, the precise familial relationships between these men is not entirely clear, but according to the 1920 Federal Census, 14 of the Bixby Hotel’s 100 residents were Ottoman Jews and of those, 13 worked as shoe shiners or bootblacks. A dozen other Sephardic bootblacks lived in the surrounding blocks: Behar Cohn and his brother Leon–who left Rhodes in 1910–lived a few blocks away with Behar’s wife and children in a small home on Crocker Street, just two houses down from bootblack Louis Benveniste, who lived with his wife Behora and their two young children as well as his brother Sam. Two other shoe-shining Benveniste brothers–Haim (Harry) and Bension–lived around the corner on 6th Street, next door to bootblack Ralph Sanna and his family and Joseph Israel, who along with his brother Leon worked as a bootblack after their arrival in 1908, lived with his wife Signora (Sadie), and their four California-born children down the street.

Whether they were kin or countrymen, these Rhodesli bootblacks helped young Louis get his first job in L.A. shining shoes. They might have given him a kit, or told him where to buy one, offered tips for the best shine, taught him a little English, or advised him on good spots to find customers. They might even have helped him get a spot at a proper stand: Louis Notrica, who himself had lived at the Bixby Hotel when he arrived in 1916, managed a bootblack parlor of his own just a few blocks away from the Bixby on Towne Street, employing for a time his brothers Albert and Elie and undoubtedly many other new arrivals to the city over the years. So too did Isaac Berro, who employed recently arrived Rhodesli Aron Benon until he left to start a shoeshine stand of his own. Shared origins, religious identity, and language provided vital sources of trust among these bootblacks, who, like those before them, worked together to secure corners in well-trafficked areas and carve out “turf” of their own. Or, to put it another way, the Rhodesli bootblacks did not need to form a union to organize themselves, as they were already bound together by tight social and cultural networks that enabled them to break into the industry.

Louis Israel did not remain a bootblack for long: he soon began buying wholesale produce to sell on the corner, eventually saving enough money to open a produce stand with fellow Rhodesli Harry Alhadeff, their “A-1 Market” growing to become a wholesale grocery supply company with headquarters at 9th Street and Towne.6 Others, like Sam and Joseph Israel, Bohor Hasson, and Leon Moskatel would purchase flats of fresh flowers in the morning from the Southern California Flower Market (just four blocks from the Bixby) and sell them from stands or on street corners until they were gone. Moskatel eventually opened a retail shop on Wall Street near the Flower Mart, which became one of the most successful florist-supply stores in Southern California. These types of low-overhead jobs, which require very little money and language skills to perform, were–and continue to be–ideal for entrepreneurial-minded recent immigrants, who are the majority of street vendors in Los Angeles today.

For others, boot blacking became a lifelong pursuit: Louis Benveniste who had left Rhodes as a young man to train as a shoemaker on the Turkish mainland and offered shines on the street after he arrived in Los Angeles in 1912, grew his business into a shoe repair and shoeshine concession inside the Bullocks department store downtown, and his brothers Alfred and Harry started their own shoeshine supply business. Benveniste maintained the business until he retired in 1960, earning enough money to purchase his own home on 51st Street and raise five children with his wife Behora.When interviewed by a reporter for the Los Angeles Times in 1923, bootblack Albert Notrica asserted that those family obligations gave his fellow immigrants an advantage in the industry:

“Our boys, we work all the time and save money. American boys think, ‘I make just enough money to have a good time.’ They don’t care about saving. They don’t care whether they give a good shine or not. We do. American boys are not married. We all married. We have to work – we have babies at home! We got to make good! We do!”7

Interestingly, Notrica–who became founding member of Sosiedad Paz i Progreso–was not identified by the reporter as a Jew or as a Rhodesli but rather as being an immigrant from Greece. This may have been a purposeful choice on Notrica’s part–a genuine expression of his diasporic identity or, perhaps, a strategic concealment of his Jewish heritage–or it might simply have reflected the author’s inabilities to differentiate between Rhodes and Greece or between Jewish and non-Jewish denizens of the region. Such confusions make it difficult to ascertain whether claims of Greek immigrants “invading” the shoe shining trade, colored by xenophobia and the resentments of the union bootblacks they displaced, were also misclassifications of Rhodeslis. More likely is that Greeks entered the industry in the same years as their Rhodesli peers, their shared regional origins and language abilities facilitating their integration. Historian Devin Naar has similarly shown that the earliest Rhodesli arrivals to Seattle had followed Greek friends there and upon arrival, socialized at Greek cafés not with other, Ashkenazi Jews.8 The camaraderie and trust among the Rhodesli bootblacks may very well have extended to non-Jewish Greek immigrants in the American context, the differences between them imperceptible to most American observers.

Even for those who had by then moved into other trades, the Rhodeslis’ shared experiences as bootblacks in their earliest days in Los Angeles provided a source of solidarity between them that reinforced and amplified their existing ties of kinship, language, and religious tradition. No wonder then that they chose to meet at the city’s only Sephardic-owned restaurant–located at 4th and Wall Streets, right next to the Bixby Hotel–to discuss how they might put that solidarity into action and work together to help their fellow Jews. Rhodeslis had played important roles in organizing the city’s first Sephardic congregation, Avat Shalom, in 1912, and comprised over half of its original member families until they split off to form their own organization. But the Sosiedad Paz i Progreso they founded in 1917 functioned as more than just a synagogue–in addition to holding religious services, originally led by hazan Reuben Israel at the home of Marco Tarica on Crocker Street, the members of the Sosiedad pooled their funds to care for members who were sick or out of work, to provide proper burials in accordance with traditional Sephardic rites to those who could not afford them, and to send financial relief to relatives in need back home. In the Sociedad, the Rhodeslis recreated the institutions that had provided the infrastructure for Jewish self-governance and autonomy in the judería–the parnassim (community council), havra kadisha (burial society), bikur holim (sick man’s fund), and ozer dalim (assistance for the poor)–and injected them with a spirit of class-consciousness and mutual-aid born of their shared experiences on the streets of downtown Los Angeles.

Citation MLA: Luce, Caroline. “The Bootblacks of Wall Street.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/bootblacks-of-wall-street/.

Citation Chicago: Luce, Caroline. “The Bootblacks of Wall Street.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/bootblacks-of-wall-street/.

About the Author:

Caroline Luce is the Associate Director of the UCLA Alan D. Leve Center for Jewish Studies… More

Citations and Additional Resources

1 “Police Nab Gang of Bootblack Bandits,” Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1911, II1, accessed at ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

2 “Barbers and Bootblacks – Many Kicking Over the Union Traces – Uniform Price Schedule is a Failure,” Los Angeles Times, Nov. 26, 1901, I5, accessed at ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

3 “Bootblacks Too: Their Union Catches the Annual Disturbance Disease and Doubles Prices of Shines,” Los Angeles Times, May 1, 1907, II1, accessed at ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

4 James Diego Vigil, A Rainbow of Gangs: Street Cultures in the Mega City (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2002), 66; Los Angeles Times, January 4, 1914, March 11, 1923, and May 17, 1925.

5 Aron Hasson, “The Sephardic Jews of Rhodes in Los Angeles,” Western States Jewish History Quarterly 4, no. 4 (1974): 241. See also Aron Rodrigue, “The Rabbinical Seminary in Italian Rhodes, 1928-1938: An Italian Fascist Project,” Jewish Social Studies, 25 no. 1 (2019): 1-19.

6 Aron Hasson, “A Rhodesli Register of Los Angeles Pioneers and a Sourcebook for Rhodesli Scholarship,” Western States Jewish History Quarterly 4, no. 4 (1974): 399.

7 Katherine Lipke, “Bootblacks and Bankers Tell Why People Fail in Business,” Los Angeles Times, March 11, 1923, III13; Hasson, “A Rhodesli Register,” 402.

8 Devin Naar, “Turkinos’ Beyond the Empire: Ottoman Jews in America, 1893 to 1924,” Jewish Quarterly Review 105, no. 2 (2015): 185.

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.