by Rachel Smith

As the great ethnic revival of the 1960s and 1970s swept across the nation, Americans around the country explored and embraced their family roots and ethnic heritage. Generations who had grown up in the United States sought out their families’ ethnic traces that had often faded, disappeared, or been forcibly cast aside as they settled into life in America. Efforts to explore their ethnic identities were bolstered by cultural, institutional, and political forces. This period saw the growth of ethnic clubs and associations, cookbooks, festivals, heritage tourism, the genealogy industry, the academic study of immigration and ethnicity, state-sponsored ethnic parades, and the restorations of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty. Together, they promoted a vision of ethnic heritage that not only resonated for individuals and families but redefined American national identity.1

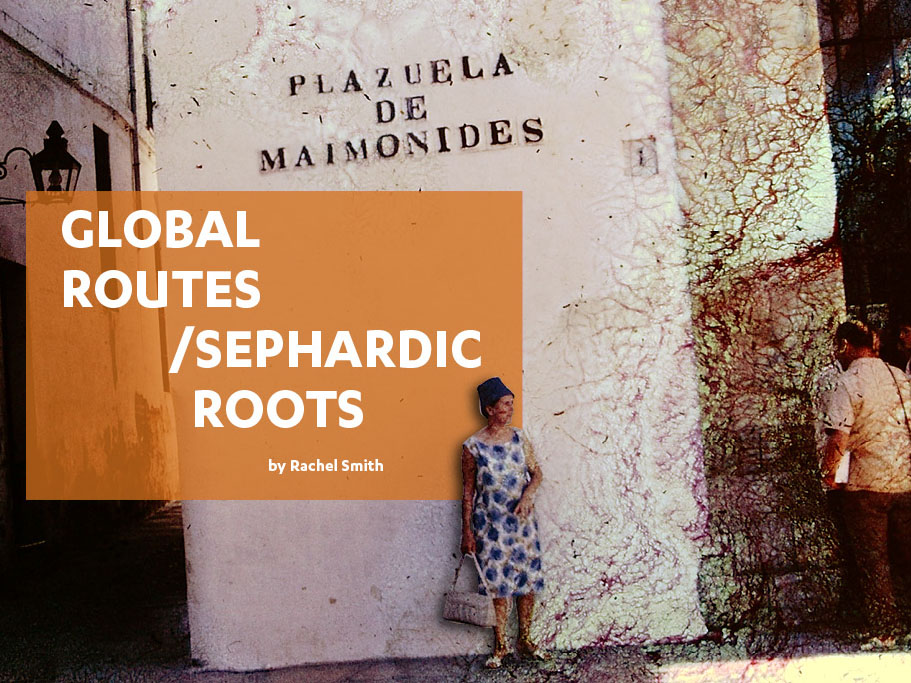

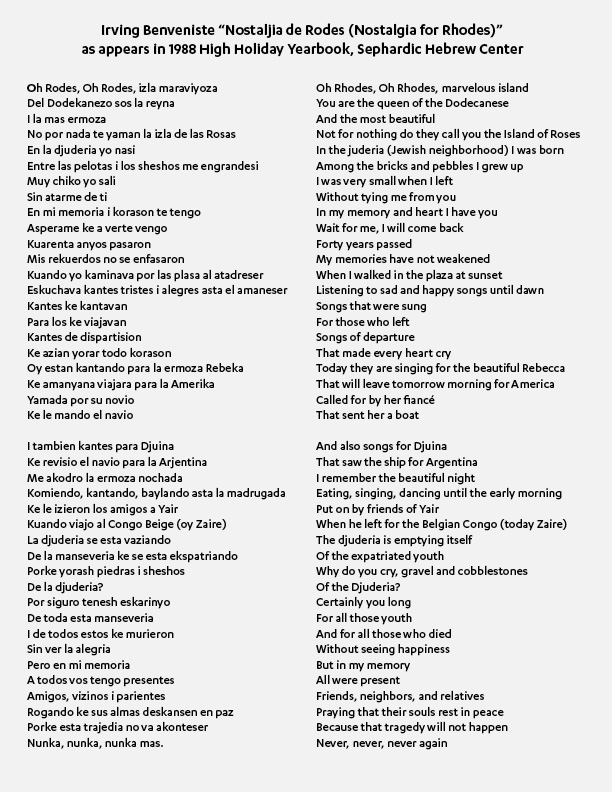

For Sephardic Jews from Rhodes living in Los Angeles, both Spain and the small Aegean island of Rhodes loomed large in the collective consciousness of the community as ancestral homelands. The first immigrant generation, who settled in Los Angeles in the 1910s and 1920s, created and sustained a globally-oriented diaspora community that maintained strong connections with Spain and Rhodes. The Sephardic Hebrew Center (SHC) hosted cultural events like “Back to Rhodes” nights and lectures on the Sephardic Jewish history by rabbis and academics. Congregants who visited Spain and Rhodes shared photos and community news gleaned from their travels in SHC newsletters. This reflected their continuing interest in their Sephardic and Rhodesli heritage and the reinforcement of that heritage in the American context.

Yet this first generation passed down to their children and grandchildren a continued, if somewhat attenuated, Sephardic Rhodesli identity. While many grew up with Rhodesli language and culture, they rarely produced it themselves. Many ate traditional foods but often did not cook them. They could often understand Ladino but few spoke it fluently. They could follow Sephardic religious rituals and prayers but could not lead them. It was these second and third-generation Rhodesli Jews who took part in the ethnic revival as it swept across the nation in the 1960s and 1970s, joining Americans around the country who established new youth groups, searched for their ancestors in genealogical records, and participated in heritage tourism that brought them to the lands of their parents and grandparents.

The stories of two young Rhodesli Jews, Art Benveniste and Aron Hasson, reflect this heightened ethnic consciousness and engagement. Both were born and raised in Sephardic families who were active in the Rhodesli community in Los Angeles. In the 1960s and 1970s, each travelled to their ancestral “homelands”: Art Benveniste embarked on a world tour to visit various communities in the Sephardic diaspora, including in Spain and Rhodes, as well as in Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo, and Aron Hasson traveled to Rhodes, a trip that would later lead him to establish the Rhodes Jewish Museum. Through these experiences, Art, Aron, and countless other Sephardic Jews who joined the search for their family roots, not only deepened their consciousness as Sephardic or Rhodesli but also participated in a nationwide process that led towards a redefinition of what it meant to be American.

A Sephardic World Tour

In June 1966, Art Benveniste boarded a cargo ship at the port of San Pedro, California with his 35mm Pentax Camera and set off on a year-long trip around the world. His journey brought him across the Atlantic to Sephardic communities in Europe, Africa, and Asia, before returning home to Los Angeles. While traveling, Art shared his impressions with his community back in Los Angeles, his writings offer an additional glimpse into his travels not captured in the many photographs he took. Further, they provided a chance for those at home reading the SHC newsletter to accompany him on his journey and to feel connected to their friends, family, and fellow Sephardic Jews around the world.

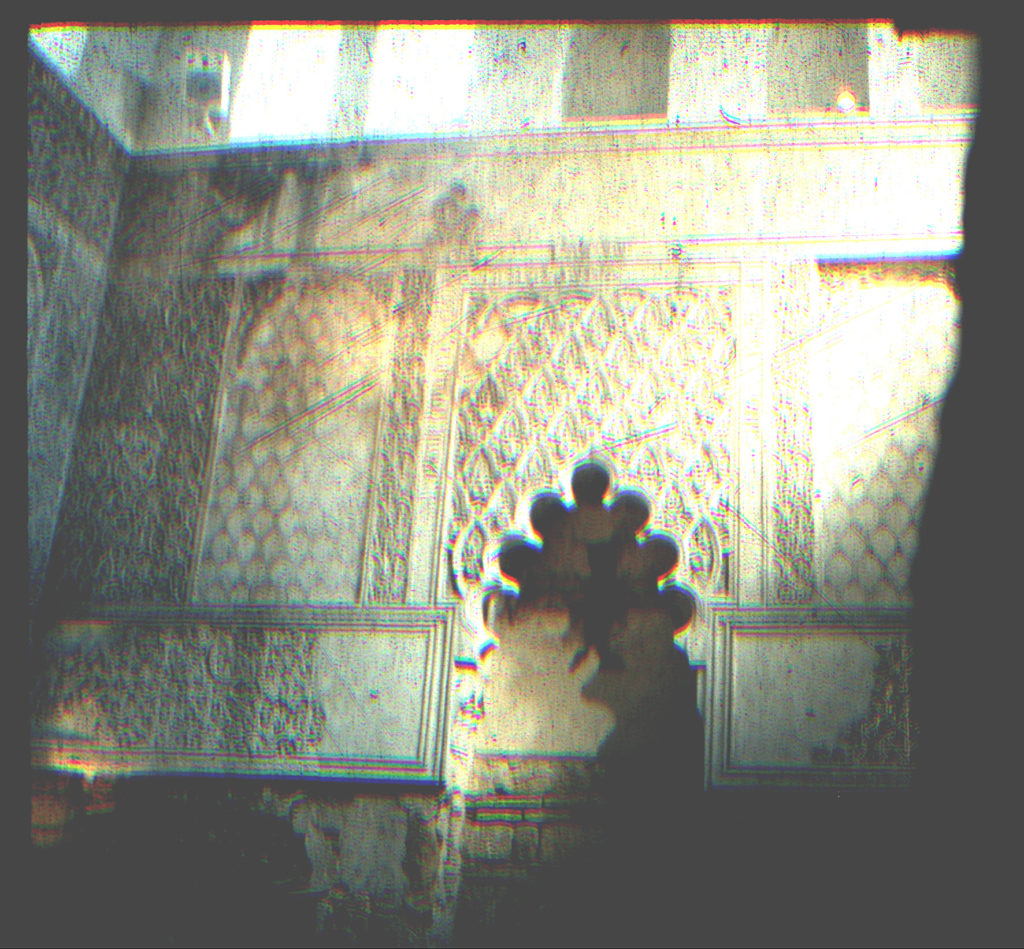

Art sailed across the Atlantic to Europe, where he visited Spain and Rhodes. In Madrid, he attended Yom Kippur services with the Sephardic Chief Rabbi of Spain and visited historic sites significant to Sephardic history, including Maimonides’ Square in Cordoba and El Tránsito Synagogue in Toledo. From Spain, he took a Turkish ship to Athens and continued on from there to Rhodes. Art’s travels to Spain and Rhodes brought him back to his familial and communal points of origin. He retraced his family’s journey from the birth of Sephardic life in Spain to the post-expulsion formation of the diasporic community in Rhodes, where his parents and grandparents were born. Art has returned to both Spain and Rhodes many times throughout his life, visiting the small communities that remain, communities that once produced and sustained a global Sephardic diaspora.

Continuing on his journey, Art made his way to the Rhodesli communities in Southern Rhodesia (Zimbabwe), the Congo, and South Africa. At the end of the nineteenth century, young Rhodesli men began migrating to Africa in search of economic opportunities. Mousa and Solomon Benatar were the first Rhodesli Jews to settle in 1895 in Southern Rhodesia, where they established Solbena, a chain of rural outposts selling supplies to farmers and miners that later grew into a thriving commercial empire. The Solbena stores popped up across Rhodesia and the Belgian Congo, serving as commercial stepping-stones for Rhodesli Jews who later immigrated and prospered in the British colony. These included Art’s uncle, who has moved from Rhodes to the Congo in the 1930s to manage a Solbena department store.

Art’s trips to the Sephardic communities in Rhodesia and the Congo coincided with decolonization, a period of political and economic upheaval in both countries. The local and national movements for independence slowed commercial activity for the Rhodesli community−long perceived as allies of the colonial authorities−prompting many to sell their struggling businesses and join established Rhodeslis enclaves in Cape Town, Ashdod, Brussels, and Los Angeles. By the time Art reached the newly independent Congo in 1966, many of his relatives had already left. But he was warmly welcomed by the tight-knit Rhodesli Jewish community that remained in Lubumbashi, where he visited with an aunt and uncle. Excited by the visit of an American “Turkino,” they hosted him at their daily lunch gatherings where they ate Rhodesli foods, spoke Ladino, and shared news. Art found that this community preserved much of the culture of Rhodes that had already begun to fade in Los Angeles, where they were more integrated into the surrounding society.

From the Congo, Art continued on to South Africa, where he visited the community of Rhodesli Jews in Cape Town, many of who had come from Rhodesia and the Congo either after independence or upon retirement. Rhodeslis in the three African states were closely connected as they moved between the different communities for economic, political, and personal reasons, transferring between branches of a company, seeking spouses, or fleeing conflict. Although all originated from one small island, these interconnected communities made Rhodeslis the largest Sephardic group with a sub-Saharan African diaspora.

These interconnections stretched to Los Angeles, where Art’s family members had sustained relationships with one another and with their ancestral lands as they settled throughout the world. His trip around the world was facilitated by the transnational networks that connected Sephardic families and communities across vast distances through correspondence, visits, marriages, and business partnerships. And by staying with them, eating with them, and touring with them—and documenting his encounters in photos and articles in the community newsletter—he helped to revive and sustain those translational networks in turn.

Return and Revival in the judería

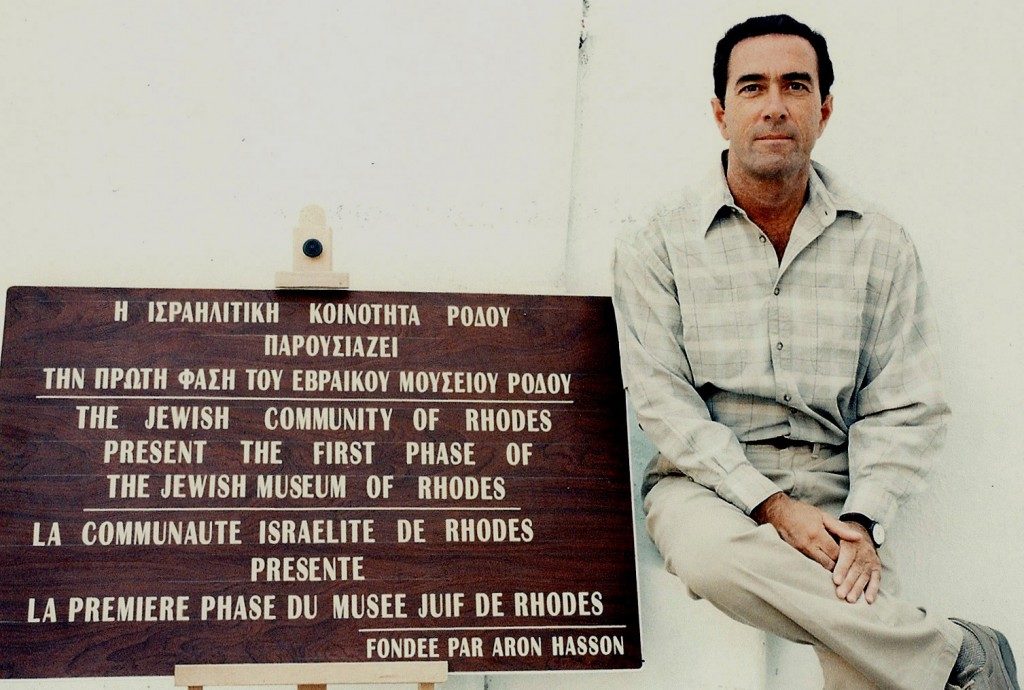

Art was not alone in his desire to retrace his family’s journey across the Atlantic and back to his ancestral homeland. Only a few years later, Aron Hasson would make his first trip to Rhodes. His four grandparents had immigrated to the United States from Rhodes between 1912 and 1920, and became active leaders in the Sephardic Hebrew Center. Aron inherited a strong connection to his family’s heritage and the South Los Angeles Sephardic enclave in which his father, one-time president of the synagogue, was raised. In 1974, Aron, as an undergraduate, also authored a short article “The Sephardic Jews of Rhodes in Los Angeles” in the Western States Jewish History Quarterly, one of the first publications ever to explore the history of the milieu in which he was raised.

Inspired by their stories and by the nation-wide ethnic revival, Aron travelled to the island of Rhodes in 1975. Walking the streets of the judería and visiting the Jewish synagogue, he connected with the island where his grandparents and generations of ancestors had once walked, prayed, and lived. The trip was a formative one, and he went home to Los Angeles with a deeper sense of his own Rhodesli identity.

Decades later, Aron returned to Rhodes with his own family to teach his children about their Rhodesli heritage, transmitting the “ethnic revival” impulse of his younger days to the next generation. Feeling the need to increase public awareness and appreciation of Rhodesli Jewish history, especially after the Holocaust, he established the Rhodes Jewish Museum and the non-profit Rhodes Jewish Historical Foundation in 1997. The museum is located in the Kahal Shalom synagogue, the oldest surviving synagogue in Greece and the only one currently in Rhodes, where the two rooms formerly used as the ezrat nashim (or women’s section) have been renovated as a museum space. It finds a companion in the website Rhodes Jewish Museum, which is a storehouse for the remarkable documents, genealogical resources, photographs, on-camera interviews, and historical memorabilia that Hasson has collected with the help of the Rhodesli Jewish diaspora. These efforts have helped revive the judería of “Rodos,” as a historical destination, supporting the tourism that continues to bring many in search of their roots. So too has the website created a digital space for Rhodesli Jews to gather, connect, and reminisce.

The popularity of the Rhodes Jewish museum reflects the collaboration of tourism and heritage: heritage transforms locations into destinations and tourism renders them economically viable as exhibitions. Scholars have noted how heritage gives buildings, neighborhoods, and ways of life that are no longer viable for various reasons a second life as exhibits of themselves. Those seeking to preserve a cultural heritage ensure the survival of places and practices that may disappear by giving them the value of historicity, exhibition, and often, indigeneity. In preserving the past, they produce something new that speaks to the needs and perspectives of the present.2

Art and Aron’s trips to Spain and Rhodes were returns to “homelands” to which they remained deeply connected despite being born centuries later and continents apart. Although they neither knew their languages nor had friends or family there, both Spain and Rhodes held a prominent place in the collective consciousness of these Sephardic Jews. The strength of this connection—rejuvenated and strengthened during the ethnic revival of the 1960s and 1970s—is one that persists today, reflected in the many Sephardic Jews now pursuing Spanish citizenship.

Tracing Sephardic migratory routes, going to old Rhodesli synagogues, and visiting friends and family in the diaspora entailed not only a search for the lives and lands of their ancestors but were processes of self-discovery. Art and Aron gained a deeper sense of belonging and appreciation for their own Sephardic culture and history through these pilgrimages to their ancestral lands. The ability of roots tourism to redefine the self unfolded on the national level as Americans around the nation embarked on heritage tours as a part of the ethnic revival. By exploring their ethnic heritage and embracing their Sephardic and Rhodesli roots, Art, Aron and countless others worked towards a new and proud reconceptualization of American national identity.

Citation MLA: Smith, Rachel. “Global Routes/Sephardic Roots.” 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce, UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020, https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/global-routes-sephardic-roots/.

Citation Chicago: Smith, Rachel. “Global Routes/Sephardic Roots.” In 100 Years of Sephardic Los Angeles, edited by Sarah Abrevaya Stein and Caroline Luce. Los Angeles: UCLA Leve Center for Jewish Studies, 2020. https://sephardiclosangeles.org/portfolios/global-routes-sephardic-roots/.

About the Author:

Rachel Smith is a doctoral candidate in the History Department at UCLA… More

Citations and Additional Resources

The author would like to thank Art Benveniste for sharing his beautiful photos.

1 Matthew Frye Jacobson, Roots Too: White Ethnic Revival in Post Civil-Rights America (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2008).

2 Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Destination Culture: Tourism, Museums, and Heritage (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998).

If you have any more information about an item you’ve seen on this website or if you are the copyright owner and believe our website has not properly attributed your work to you or has used it without permission, we want to hear from you. Please email the Leve Center for Jewish Studies at cjs@humnet.ucla.edu with your contact information and a link to the relevant content.